(沉默的)观看之道与政治寓言

Seeing comes before words. The child looks and recognises before it can speak.

重读《观看之道》,没想到这也是一本当今数字监控时代的政治寓言。虽说一千人眼中,有一千个哈姆雷特,早已是陈词滥调,但其中蕴含的道理仍不过时。只是哈姆雷特如今是什么样貌,取决于我们身在何处,从哪里出发。

书中所言,观看先于文字,就像孩童在牙牙学语前,早就瞪大个眼睛,四处观看辨识周遭的世界了。

But there is also another sense in which seeing comes before words. It is seeing which establishes our place in the surrounding world; we explain that world with words, but words can never undo the fact that we are surrounded by it.

当然,除开如此浅显的意思,是观看先建立了我们存于世界的位置,然后我们再用文字/言语来解释这一切。因而是观看,让我们有了“周遭”。这并非是说文字不重要,我们使用文字来表达,诠释,描绘和虚构我们的所见所闻。但没有了文字,我们所看的,我们的周遭,并不会因此而消失。那么,这是不是可以说,所写无法否认和消灭所看。文字和言语,宣传和鼓动,可以影响我们看什么,我们如何去看,但不可否认,我们与这真假难辨的一切的遭遇,是因为我们在看着。

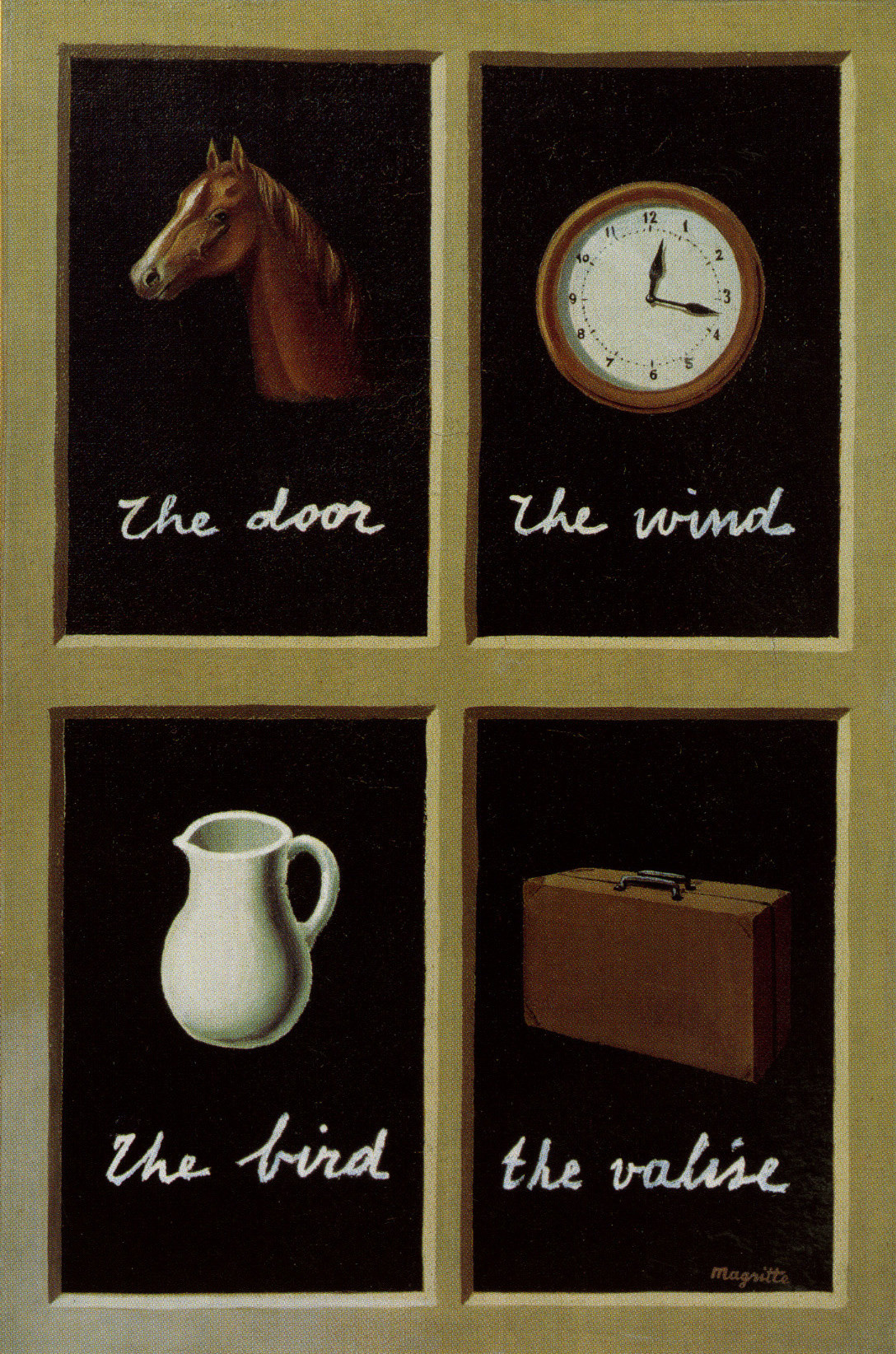

The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled. Each evening we see the sunset. We know that the earth is turning away from it. Yet the knowledge, the explanation, never quite fits the sight. The Surrealist painter Magritte commented on this always-present gap between words and seeing in a painting called The Key of Dreams.

但我们所看到的和我们所知的并不等同。所看与所知的关系总是在变化,我们好像永远也没法将我们所看的与所知的完全对上。我们看到太阳东升西落,于是我们说,太阳升起来了。但其实我们知道,太阳是不会升起来的。是我们的仰望,我们的观看,如此以为。而我们的所知告诉我们,这是地球的自转。因此,文字与直观之间永远有一条补不上的缝隙,让我们没法讲到底:我们到底看到了什么,又到底从中知道了些什么。超现实主义画家,马格里特的画作 The Key of Dreams 就是这么一个评论的问号,画在了所知与所看的等式之间。

The way we see things is affected by what we know or what we believe. In the Middle Ages when men believed in the physical existence of Hell the sight of fire must have meant something different from what it means today. Nevertheless their idea of Hell owed a lot to the sight of fire consuming and the ashes remaining- as well as to their experience of the pain of burn.

When in love, the sight of the beloved has a completeness which no words and no embrace can match: a completeness which only the act of making love can temporarily accommodate.

所看与所知总是相互影响。这其中少不了,相信的力量。这力量可不小,足以改变地狱和火焰。中世纪时期笃定地狱存在的人们看到熊熊烈火时,心中的印象应该与现在的人所看到的火焰大相径庭吧。如果没有见过烈火,没有看到过大火燃烧之后,寸草不生,满地焦痕,没有体验过灼烧,又如何想象、相信末日与地狱呢?

但我们总是少不了要相信点什么吧?我们相信我们所看到的,有时就是这么简单。可这却引来了深深的矛盾,哪怕只是字面上的。因为我们常常说,人们盲目相信... 但有时却是看到了才相信的啊!现今的反智主义在信息的茧房中,在柏拉图的洞穴中,坚信他们的所见。也许在这时候,所见就真成了所知。

Yet this seeing which comes before words, and can never be quite covered by them, is not a question of mechanically reacting to stimuli. (It can only be thought of in this way if one isolates the small part of the process which concerns the eye's retina.) We only see what we look at. To look is an act of choice. As a result of this act, what we see is brought within our reach- though not necessarily within arm's reach. To touch something is to situate oneself in relation to it. (Close your eyes, move around the room and notice how the faculty of touch is like a static, limited form of sight.) We never look at just one thing; we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves. Our vision is continually active, continually moving, continually holding things in a circle around itself, constituting what is present to us as we are.

所幸,观看总为我们留有余地,再贪婪暴力的文字都填不满。在观看与文字之间的空隙即自由。观看绝不是唯物的,除非我们硬是要剥开生活与万物间的联系,改造世界,只谈一个原子的“科学”。观看是一种选择,我们只看到我们所选择看到的。因而当我们闭眼不看,闭而不听时,我们其实也是在选择我们的周遭,我们的世界。周围的墙的砖瓦是我们自己添的,我们的自身也随之而改变。因为,我们能所见的,我们选择所见的,我们观看的方式,永远将我们与周遭紧密联系在一起。我们从来不是看单个的事物,我们所看的,不管明显与否,都是一种关系,一种联系。

Soon after we can see, we are aware that we can also be seen. The eye of the other combines with our own eye to make it fully credible that we are part of the visible world. If we accept that we can see that hill over there, we propose that from that hill we can be seen. The reciprocal nature of vision is more fundamental than that of spoken dialogue. And often dialogue is an attempt to visualise this-- an attempt to explain how, either metaphorically or literally, 'you see things', and an attempt to discover how 'he sees things'.

当我们在看山时,也理应假想当我们站上山头时,我们也能眺望到刚刚在远处观望的自己。我们的眼睛里永远有倒影。当我们想看到自己时,必须要望向别处,不管是镜子,还是别人的眼睛。主动与被动,在观看中,成了相互包含的关系。我们的视线,在不断的移动中,将事物联系起来;周遭在改变,在流动,我们也是。在这个意义上,观看即行动,即使沉默。